Iran’s Changing Media Landscape: YouTube Channels and VOD Platforms

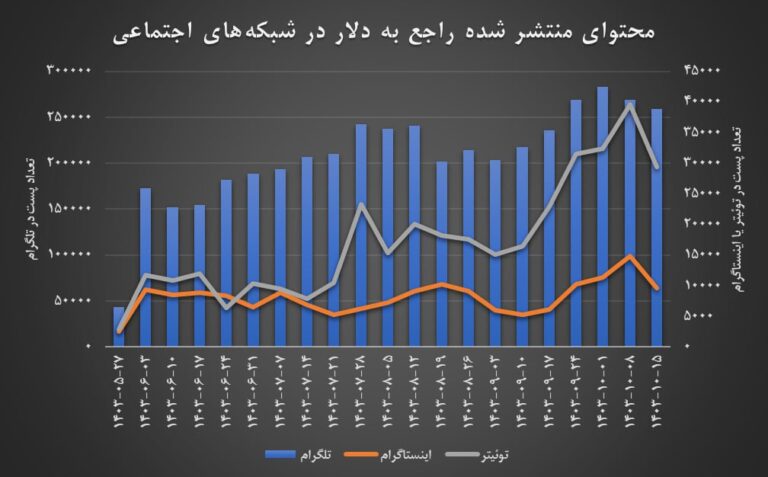

YouTube interviews with Iranian politicians and activists, along with video-on-demand (VOD) cultural programs and TV series on domestic platforms, have largely emerged as products of the 2022 Women, Life, Freedom movement.

Since then, despite technological and ideological challenges, Iranian producers have persistently pushed back against state censorship and traditional taboos, reshaping the country’s tightly controlled media landscape.

A Love-Hate Relationship with the Government

The government’s response to these online productions has been ambivalent. While it occasionally supports their creation and acknowledges their utility, it strongly opposes any challenge to state television’s exclusive broadcasting rights, as enshrined in the constitution. YouTube interview channels, in particular, draw criticism when they cross red lines such as questioning the Supreme Leader’s authority. Nevertheless, the government views their popularity as a useful counterbalance to foreign-based Persian-language television.

Cultural VODs, especially drama series and comedic reality shows, have become a thorn in the side of the deeply unpopular state broadcaster, IRIB, which also oversees VOD content censorship. According to Fars News Agency, IRIB chief Payman Jebelli has urged the Judiciary to prosecute “lawbreakers” in this space, despite the absence of any applicable laws. He has also called for a ban on airing videos that lack a production license from state TV.

These programs, along with political talk shows on YouTube, enjoy widespread popularity and offer a refreshing alternative to the monotonous and heavily censored state broadcasts. Viewers embrace them, even though access often requires paying subscription fees, using VPNs, or incurring high data charges especially for YouTube videos longer than an hour.

From the government’s perspective, allowing limited access to these platforms is a strategic move. Following the 2022 unrest, officials were advised to keep citizens engaged and foster dialogue across political lines. Lightly censored comedies and dramas are seen as a way to placate public sentiment, while political talk shows offer a controlled space for discourse.

Domestic Platforms and Bold Storytelling

Platforms like Filimo and Namava have produced ambitious series, including:

- Sovashoon, a 1960s period drama with subtle xenophobic undertones directed by Nargess Abyar.

- Tassian, a love story set against the backdrop of the 1979 revolution, directed by Tina Pakravan.

- At the End of the Night, widely regarded as the first motion picture to portray the realities of modern Iranian life, directed by Aida Oanahandeh.

Notably, all three were directed by women, received acclaim from viewers, and drew sharp criticism from hardliners.

Political Talk Shows: The Rise of the “Independents”

YouTube’s political talk shows are produced by three distinct groups, with the “Independents” being the smallest. This group consists of a handful of individuals who, unlike other producers, have not been publicly linked to the government, intelligence services, or political organizations.

Ironically, some independents, like the outspoken and often controversial Javad Mogooi, are rumored to have ties to “the core of the system.” Mogooi, known for his critical documentaries, now hosts a talk show where he interviews high-ranking officials, including the Foreign Minister and senior IRGC commanders like Aziz Jafari and Yahya Rahim Safavi, both advisers to Supreme Leader Khamenei.

Mogooi stands out for his commanding presence and willingness to challenge powerful figures, eliciting candid discussions rarely heard in public discourse. Most other anchors, often current or former journalists, remain cautious under government scrutiny.

On the opposite end of the spectrum are reformist voices like Mehdi Mahmoudian, a former political prisoner whose Patt Studio was shut down by authorities, despite the fact that YouTube channels remain outside formal government regulation. Mahmoudian has vowed to continue production anyway.

Other notable independents include the cautiously critically minded Azad Dialogue channel, investigative journalist Yashar Soltani, and sociologist Mohammad Fazeli. While they primarily use Telegram for its ease and accessibility, they also maintain a presence on YouTube.

The programming of private outlets typically features interviews with political figures, focusing on current affairs, especially social and economic issues. Occasionally, they tackle sensitive cultural topics such as the compulsory hijab and its impact on daily life in Iran. These productions appear to target audiences both inside and outside the country. None of them are politically neutral; each reflects distinct factional interests. A recent example is Khabar Online’s hijab debate, which went viral due to participants shouting over one another.

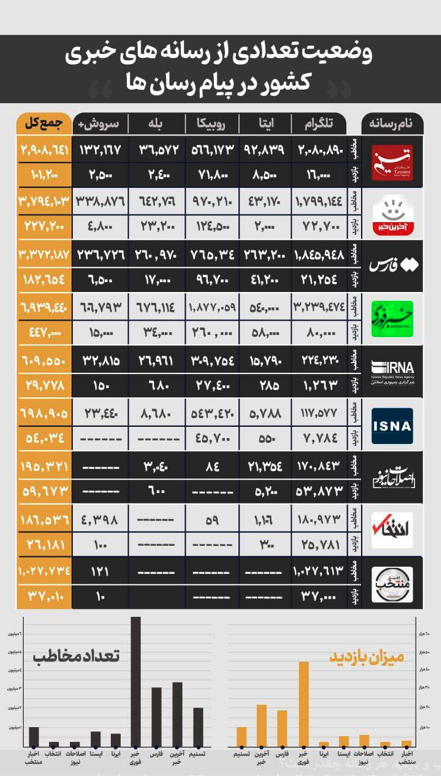

Media Organizations in Iran’s Evolving Digital Landscape

Nearly all Iranian private and government-owned media organizations, —from the IRGC-linked Tasnim News Agency to relatively moderate conservative outlets like Khabar Online and pro-reform platforms such as Entekhab—have embraced the production of long- and short-form documentaries, interviews, and often controversial political talk shows. These outlets are frequently connected to current and former officials, including Security Chief Ali Larijani and former President Hassan Rouhani. Another group of media organizations are government-owned and strictly government controlled.

A key observation is that while relatively independent outlets like Khabar Online may promote narratives that diverge from the official line, government-linked platforms—including YouTube channels operated by state-owned agencies such as ISNA and IRNA—largely echo state propaganda.

Some state-owned YouTube channels, including the Basij-affiliated Student News Network (SNN) and Hamshahri, function like traditional TV stations, offering news and current affairs content for long hours. Their tone is often more hardline than the public stance of government officials. Despite their limitations, these channels occasionally provide exclusive footage that foreign-based Persian media cannot access otherwise. While they aim to influence diaspora media narratives, foreign outlets typically sidestep their political framing and repurpose the footage with their own editorial slant.

Among the most active and productive outlets in this space are privately owned Entekhab, Khabar Online, Fararu, and Sharq Newspaper as well as government and military owned SNN, Tabnak, , and agencies such as IRNA, ISNA, Mehr, Tasnim, Fars, and the IRIB-affiliated Young Journalists Club (YJC).

Tone and Narrative

The tone varies widely across outlets:

- Government-owned agencies like IRNA and ISNA maintain a relatively neutral and factual tone.

- Hardline platforms such as Tasnim and Fars adopt a radical, sensational, and aggressive style.

- Pro-reform outlets like Fararu and Entekhab tend to be cautious, analytical, and occasionally sarcastic.

For example, in coverage of negotiations with the West:

- IRNA described the process as “step-by-step progress.”

- Tasnim headlined with “America Drowns in Ukraine Quagmire.”

- Reformist outlets focused on the talks’ impact on currency exchange rates.

Interviewees and Topics

Each outlet tends to feature guests aligned with its political stance:

- IRNA and similar platforms interview state officials.

- Hardline channels host IRGC commanders and conservative politicians.

- Reformist outlets engage with analysts like Abbas Abdi and Saeed Laylaz.

Topic selection also reflects political leanings

- Government-linked channels highlight foreign policy “achievements.”

- Hardliners emphasize resistance, external threats, and alleged reformist corruption.

- Reformist platforms explore economic challenges and social issues.

Video Length and Format

- Government-owned agencies typically produce clips lasting 5–10 minutes.

- Hardline outlets feature videos ranging from 30 minutes to an hour.

- Pro-reform channels often exceed one hour, with some episodes running over two hours.

Viewership and Revenue

Due to internet censorship and the YouTube ban, viewership figures remain modest:

- IRNA, Fars, YJC, and Hamshahri average under 10,000 views.

- Entekhab surpasses 14,000.

- Tasnim leads with 437,000 views.

Fairly independent YouTube channels attract between 10,000 and 200,000 views, depending on the topic. During times of national crisis, viewership can spike dramatically.

External sources estimate combined revenues for VOD platforms Filimo and Namava at over $260 million, though no independent figures exist for YouTube channel earnings. Namava claims 14 million viewers, while Filimo reports around 10 million.

In comparable markets, YouTube producers earn between $0.50 and $2 per 1,000 views. However, official revenue data for Iranian creators is unavailable.

State Control and Censorship

While some online activities—such as webcasting and YouTube uploads—are not formally regulated, producers operate under constant scrutiny. Legal repercussions, including imprisonment, remain a real threat.

Journalists report that intelligence agencies have offered partial funding to creators who respect red lines. During an interview with an “independent” channel, political analyst Sadeq Zibakalam remarked on the studio’s lavish setup, suggesting it was likely government-funded.

VOD production companies, often well-connected, have resisted censorship by leveraging support from one government body (e.g., the Ministry of Culture) to counter pressure from another (e.g., state TV). Their financing typically comes from Tehran-based startups, some affiliated with the IRGC.

Meanwhile, YouTube creators with opaque funding sources must “behave” to secure reliable internet access and government facilitation for repatriating their share of YouTube ad revenue. This subtle manipulation—through control of financial and technological levers—is the government’s refined method of enforcing censorship.